Fitness

"Play Your Way to a Healthier You"

What does it mean to be Fit?

Many people strive to be fit. Fitness, after all, is synonymous with health, but what exactly does it mean to be fit?

There are many definitions and individual perceptions of ‘fitness’. While some might associate fitness with excelling in competitive activities, for our purposes, I will define fitness as the capability to carry out everyday tasks comfortably and with vigour. This kind of fitness can be referred to as ‘health-related physical fitness’ – having a healthy heart, strong muscles, and good mobility. Although this website only deals with health-related physical fitness, it is well-known that exercise (what you do to improve your fitness) also have a positive psychological effect, by promoting mental, social and emotional well-being.

Maintaining a good level of physical fitness is important. Having a high level of overall fitness is linked with a lower risk of chronic disease, better ability to manage health issues that do come up, and greatly improved functionality and mobility throughout your life span. In the short term, being active also improves your day-to-day functioning, from better mood to sharper focus to better sleep.

Simply put: Your body is meant to move, and it functions much better when you’re fit.

Components of Physical Fitness

Physical fitness can be divided into three intersecting components that can be broadly grouped into Metabolic fitness, Health-related and Skill-related. An individual’s level of ‘fitness’ in each of these components can be assessed, and adjusted through targeted exercise programmes.

Metabolic Fitness

Metabolism is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions that occur within the body in order to maintain life. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the conversion of food to building blocks for proteins, lipids (fats), nucleic acids (DNA), and some carbohydrates; and the elimination of metabolic wastes. The liver, endocrine system (hormones), and lymphatic system of the gut play significant roles in supporting the digestive system during these metabolic processes.

Metabolic Fitness is a measure of the body’s health when at rest. It is not a predetermined trait, but reflects your current state of health. The body is a dynamic machine and metabolic optimization is a continual process that requires effort and consistency. Clinically speaking, metabolic health is defined by optimal levels of various markers, such as blood pressure, blood sugar (glucose) levels, triglycerides, cholesterol levels, and waist circumference – without the use of medication. Metabolic fitness is basically the component of physical fitness that deals with how your body responds to food and exercise – i.e. satisfying the body’s energy demands.

There is no official definition for the term metabolic health. Some experts claim metabolic health is simply the absence of metabolic syndrome and a low risk of developing metabolic diseases. A metabolically healthy body can effectively process food without causing unhealthy spikes in blood sugar, insulin, cholesterol, or inflammation. Avoiding these spikes is crucial because they can lead to long-term health problems, including insulin resistance, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, all of which raise the risk of chronic diseases. In the short term, poor metabolic health can lead to low energy, impaired brain function, memory, mood, skin health, and fertility.

Glucose is a primary precursor for energy in the body, and needs to be tightly regulated for metabolism to function effectively. Metabolic health can be improved by consistently making choices that keep glucose levels stable within a healthy range, minimizing major fluctuations. These choices may involve selecting foods that don’t cause significant spikes in glucose and improve glucose processing, maintaining a regular exercise routine, getting quality sleep, managing stress, and avoiding environmental toxins known to disrupt metabolic function.

Health-related Fitness (aka Physiological Fitness)

Good health has a strong relationship with health-related components of physical fitness because it determines your ability to carry out daily activities with vigour, and exhibit qualities associated with low risk of premature development of hypokinetic (low levels of movement) diseases. The components of health-related fitness include Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Muscular Strength, Muscular Endurance, Flexibility and Mobility, and Body Composition.

• Cardiorespiratory Fitness

Cardiorespiratory Fitness (aka Cardiovascular Endurance) is related to the ability to perform large-muscle, whole-body exercise at moderate to high intensity for prolonged periods. Terms commonly used to denote this component of physical fitness includes Aerobic Fitness and Aerobic Capacity. Cardiorespiratory fitness is the ability of the heart and lungs to deliver oxygen to the working muscles and for muscles to use this oxygen to do work, and is measured as the maximum volume of oxygen (VO2max) that can be delivered to those muscles during exercise.

The best types of exercise for improving cardiorespiratory fitness are those that involve the use of large muscle groups over a prolonged period of time at an intensity that is classed as aerobic, such as brisk walking (±100 steps per minute), hiking, running, cycling, swimming, dancing, etc. As the intensity of the exercise increases, the amount of oxygen required by the muscles to cope with the demands increases; therefore, the heart rate increases in proportion.

The most important health benefit associated with an increase in cardiorespiratory fitness is a reduced risk of Coronary Artery Disease by improving your cholesterol and blood pressure levels.

• Muscular Strength and Endurance

Muscular Strength and Muscular Endurance are two important aspects of your body’s ability to move, lift things and do day-to-day activities. Muscular strength is the amount of force a muscle or muscle group can put out over a short period of time, or the amount of weight you can lift. Strong muscles contribute to better posture, stability, joint support and balance. Strengthening muscles can make everyday activities like lifting groceries or picking up children much easier and safer.

Muscular endurance is the ability of your muscles to sustain repeated contractions over a prolonged period without getting tired. For instance, having good muscular endurance enables you to go for longer walks, perform more repetitions during exercises, and complete tasks without getting exhausted.

Both muscular strength and endurance have a direct impact on your quality of life by contributing to enhanced mobility, reduced risk of injuries, and greater functional independence as you age. Additionally, building muscle mass can boost your metabolism, aiding in weight management and promoting overall health. Muscular strength and endurance can be developed through resistance training. This involves working a muscle or group of muscles against resistance to increase strength and power. A gym or fitness centre is a good place to go if you’re interested in doing resistance training.

Of course, you don’t have to go to a gym or buy exercise equipment to improve muscular strength and endurance. Doing normal daily activities like lifting groceries or walking up and down stairs can also help. You can also do many exercises at home that don’t need equipment, such as push-ups and sit-ups. All you have to do is challenge your muscles to work harder or longer than they usually do.

• Flexibility and Mobility

Flexibility is the ability of tendons, muscles and ligaments to stretch sufficiently to allow joints to move through their full range of motion (mobility) without pain, which is fundamental for carrying out everyday activities. Mobility also includes factors like stability, coordination, and balance in addition to range of motion.

There are many factors that can lead to decreased joint mobility, such as injuries, medical conditions and aging. However, there are many things we can do to help prevent a decline in joint mobility, including regular exercise or simply being more active throughout the day, maintaining a healthy weight, proper posture, avoiding overuse and repetitive movements, proper nutrition and staying hydrated.

Maintaining good joint flexibility and mobility requires a well-balanced exercise routine that includes a range of different types of exercises. Pilates, Yoga, Tai Chi and Qigong are popular practices that can contribute to improving your strength, balance, flexibility and posture.

• Body Composition

Body Composition refers to the ratio of fat, bone and muscle within the body. Even though it is listed here as a component of fitness, body composition primarily serves as an indicator of your overall state of health. Excessive body fat is linked to various health conditions, including hypertension (high blood pressure), hyperlipidaemia (high cholesterol), diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and an increased susceptibility to certain cancers such as colorectal, post-menopausal breast, uterine, oesophageal, kidney, and pancreatic cancer.

Body fat can be divided into two categories:

- Essential fat – This type of fat is found in your brain, bone marrow, nerves and the membranes that surround and protect your vital organs. Essential fat plays a key role in hormone regulation, including the hormones that control fertility, vitamin absorption, and temperature regulation. For women, a healthy range is about 10 to 13 percent of body composition from essential fat, while men typically require 2 to 5 percent.

- Stored fat – This kind of fat is predominantly found in adipose tissue under the skin (subcutaneous fat), but also in your abdomen and around all the major organs (visceral fat or “belly fat”), such as the liver, kidneys, pancreas, intestines and heart. Stored fat is vital for your body to function normally. It serves as energy reserves, insulates and cushions the body. A certain amount of subcutaneous fat is normal and healthy, but too much can lead to imbalanced hormone levels and have a detrimental effect on hormone sensitivity. Elevated levels of visceral fat increases your risk for diabetes, heart disease, stroke, artery disease, and some cancers.

If you are between 20 and 39 years of age, you should aim for a total body fat range of 21 to 32 percent for women and 8 to 19 percent for men. An acceptable range for people over 40, is between 23 and 35 percent for women and 11 to 24 percent for men.

From a fitness perspective, excess body fat lowers your work to weight ratio, meaning a heavier individual expends more energy per minute of activity, resulting in lower energy efficiency during exercise. Furthermore, surplus body fat places additional load on joints causing joint distress.

Skill-related Fitness

Skill-related or Performance-related Fitness, often simply referred to as Motor Skills, encompasses a set of vital abilities including balance, co-ordination, agility, speed, power, and reaction time. Although typically associated with skill-related fitness, these components should be integrated into everyone’s Health-related fitness regimen, especially for older people. These skills are crucial for performing everyday activities, ranging from basic tasks like walking and climbing stairs, to more intricate movements such as engaging in sports or dancing.

As we grow older, a range of chronic conditions like arthritis, as well as a natural decline in motor skills, can lead to decreased mobility and independence. Nonetheless, regular physical activity and exercise can play a pivotal role in combating this decline. By making exercise a central part of a healthy lifestyle, you will not only preserve your motor skills but also take pleasure in a more active and rewarding life, regardless of your age.

Factors Influencing Physical Fitness and Exercise

Regular exercise is one of the best things you can do to improve your health, and stay healthy for longer as you get older. When you start exercising regularly, you will quickly begin to feel and see the benefits it has on your body and well-being. However, before you start an exercise regime, there are a number of important things to think about.

• Your Current State of Health and Fitness Level

It is very important to assess your health before starting any exercise routine, particularly if you have not been active for a while. If you are taking any medication, have bone or joint problems, have diabetes or heart disease it is a good idea to discuss your fitness goals and planned exercise routine with your doctor first, as these problems might get in the way of what you want to achieve.

Assessing your current level of fitness includes checking your strength, endurance, flexibility, range of motion, and more. Checking these stats will enable you to figure out where to start and where to go from there. Just saying “I’m out of shape” isn’t specific enough when determining what you need to work on. You need to be more specific. For example: Can you walk 5km at a reasonable pace without getting out of breath? Do you find it hard to hold a plank for one minute, or can you keep it up for more than two minutes? Can you do one push-up, or perhaps fifty? For how long can you hold a ‘wall-sit’ position while breathing freely?

Starting with the wrong exercise intensity can be a waste of time, or a recipe for injury. Luckily, there are many simple Fitness Tests you can do at home. Below, are two links to internet resources that will help you to determine your current level of fitness.

• Age

Although no amount of physical activity can stop the biological ageing process, it is powerful tool for safeguarding health and mobility as you age. However, older adults face a higher risk of exercise-related injuries. Overuse injuries, fractures and damage to cartilage or ligaments can interrupt fitness progress, and it can be hard to bounce back. The good news is that understanding your body’s limitations and cultivating healthy habits can considerably reduce such injuries.

Why Age Matters

Most people begin to experience bone, muscle and cartilage loss, and encounter joint and tendon issues sometime around their mid-40s to early 50s. Lifestyle factors like poor diet, inactivity, smoking, and excessive alcohol use accelerate this loss and weakening of these tissues, increasing susceptibility to exercise-related injuries. For example, reduced muscle mass affects balance, raising the likelihood of falls. A decrease in cartilage around joints causes stiffness and pain, while aging tendons become more susceptible to tearing with strain.

Furthermore, healing from injuries takes longer as people reach older middle-age and beyond. Factors such as increased inflammation, less efficient cellular repair, and hormonal changes, like those during menopause, contribute to slower healing.

Common Exercise Injuries in Older Adults

Individuals aged 50 and above are more prone to exercise-related injuries compared to younger adults. Some frequent injuries include lower back pain from natural wear and tear, too much sitting or excess weight; overuse injuries like tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis) and tendonitis; osteoarthritis commonly affecting hip and knee joints; rotator cuff (shoulder joint) and meniscus (knee) tears; and stress fractures, often in the lower leg and foot.

Exercises Seniors Should Approach with Caution!

- Abdominal crunches/sit-ups can strain the back and spine, leading to painful injuries. Opt for safer alternatives like leg lifts and planks.

- Squats exert excessive pressure on knee joints and may also cause balance issues, increasing the risk of falls.

- Long-distance running can stress joints and the cardiovascular system. Consider low-impact alternatives like brisk walking, cycling or swimming.

- Stair climbs (for exercise) can strain knee and foot joints, as well as leg muscles.

- Leg presses can harm spinal discs due to pressure on the spine.

- Deadlifts can be taxing on the back, arms, and shoulders, and are not recommended for seniors.

Safer Exercise Strategies

Unfortunately there are no guarantees with physical activity. Regardless of the precautions you might take, injury will happens. However, these strategies can help minimize risks:

- Find an Enjoyable Activity and Stick with It: As we age, some decline in strength and fitness is natural. However, engaging in regular physical activity can help maintain a higher fitness level compared to a sedentary lifestyle. Thus, discovering an exercise routine that you enjoy and committing to it most days of the week is essential.

- Be Aware of Your Limits: What worked for you at 25 might not be suitable at 60. Be open to adjusting your exercise routine to fit your current age. For instance, if high-impact workouts are regularly causing pains and strains, consider transitioning from running to walking or swimming.

- Embrace Strength Training: Strength-building is not limited to lifting weights. Resistance bands, yoga, and even everyday tasks like carrying groceries can help build and maintain muscle strength.

- Include Balance Exercises: Enhancing balance reduces the risk of falls during physical activities and in daily life. Yoga, Pilates, tai chi, or simple exercises like marching in place can help. If needed, having a chair or support to hold on to can aid in maintaining balance.

- Prioritize Stretching: Incorporating gentle stretches before and after exercising supports flexibility of muscles and joints, and lowers the risk of injury.

- Ensure Adequate Sleep: Generally, older adults need 7 to 9 hours of sleep per night. However, after an intense workout, you might require up to 10 hours to aid recovery.

Staying Active Can Help You Stay Healthy

The bottom line? Taking care of your muscles, bones, and joints can help avoid injuries, so you can stay active and support your health for longer.

Sources:

- Desmond, M. (2023). What older adults need to know about exercising safely. Temple Health. https://www.templehealth.org/about/blog/what-older-adults-need-to-know-about-exercising-safely

- 6 Risks of exercise for older adults & how to avoid them. (2023). Maximum Fitness Center in Vacaville, CA. https://www.maximumfitnessvacaville.com/blog/what-6-exercise-seniors-avoid-risks

• Gender

Both women and men can achieve a high level of fitness, but the nature of that fitness may differ due to the unique attributes of each gender. Men and women have very different levels of hormones and, consequently, body composition, which influence their fitness journey. For the best fitness outcome, it is important to tailor your workout routine to suit your gender, body type, and personal fitness goals.

Research in genetics shows that men and women express many skeletal muscle-related genes differently. Before puberty, there’s no significant disparity in muscle strength between boys and girls. However, the sex hormones (androgens, estrogens and progesterone) play a pivotal role in triggering gene expressions that lead to the development of secondary sex characteristics, including larger muscle mass in males (1, 2).

Generally, men have larger body frames and higher testosterone levels compared to women. Higher testosterone levels in men are linked to building muscle and losing weight, resulting in typically leaner and stronger physiques. The larger bodily framework in men contributes to having comparatively bigger hearts and lungs, beneficial for cardiovascular exercises.

Oestrogen causes women’s bodies to store more fat compared to men. This biological difference serves the purpose of enhancing women’s capabilities for childbearing. However, this tendency to store fat can pose a challenge for women in their weight loss endeavours.

As a general rule, men often excel in strength and speed-based sports, while women tend to have an edge in endurance activities. Women’s reliance on aerobic metabolism allows them to sustain a steady state workload for longer, resist fatigue better, and recuperate faster between sets compared to men (3). In terms of energy usage, women’s bodies prefer utilizing fat, while men’s bodies typically use a higher proportion of carbohydrates, alongside protein and fat. This highlights the crucial role of nutrition, particularly for women aiming to lose weight (4).

Physiologically, women possess longer and more elastic muscles, enabling them to outperform men in tasks requiring flexibility. This difference sometimes restricts men from achieving optimal form and body positioning during complex movements. Therefore, men should dedicate more time to stretching exercises to enhance muscle elasticity and range of motion, ultimately preventing injuries.

However, these differences do not mean women should train differently than men. Women will be naturally better in endurance situations and men will usually be stronger and faster. However, due to women’s comparatively smaller and weaker bone structure, incorporating weight training into their fitness routine is crucial to enhance bone density (4). Generally, both men and women benefit from following similar principles: regular strength or weight training to support muscle and bone health, a nutrient-rich diet, sufficient rest to avoid overtraining, and aerobic activities to complement a foundational strength program. Nutrition and lifestyle factors, including adequate sleep, avoiding overtraining, and daily movement, contribute significantly (up to about 80 percent) to the results seen in fitness endeavours, so starting with these aspects is the way to go (5).

Gender Disparities in Aging and Physical Activity: Implications for Health and Exercise Strategies

While engaging in regular physical activity offers health benefits across the life span, fewer people tend to meet the required activity levels as they age. With aging comes an increase in chronic health conditions and physical limitations. Notably, among adults aged 50 and above, women are less likely than men to engage in sufficient physical activity for reaping these health benefits. Additionally, the aging process and associated health conditions often differ between genders, with women tending to live longer but experiencing more health issues (6).

Aging is commonly associated with physiological changes such as declining bone density, reduced muscle mass, increased body fat, particularly the accumulation of fat around the abdominal area (central adiposity). Menopause can exacerbate these changes in women, potentially accelerating the physiological decline linked with aging and a sedentary lifestyle. Postmenopausal women also exhibit a higher incidence of metabolic syndrome, characterized by various cardiovascular risk factors like obesity, high cholesterol, hypertension, and elevated fasting glucose levels. These changes partly stem from alterations in body composition and reduced physical activity levels. Sarcopenia, the age-related reduction in muscle mass, leads to decreased physical function, slower walking speed, balance issues, decreased bone density, and a lower quality of life. Engaging in regular physical activity can play a vital role in counteracting these age-related physiological declines. It can enhance longevity and lower the risk of metabolic and chronic diseases (7).

For women experiencing menopause and beyond, adopting a comprehensive health plan that includes lifestyle adjustments is vital. Exercise should form a crucial part of this strategy, offering numerous benefits like maintaining muscle and bone mass and strength. The exercise regimen for postmenopausal women should encompass endurance (aerobic), strength (resistance), and balance exercises, aiming for at least two and a half hours of moderate aerobic activity each week. Additionally, practices like deep breathing, yoga, and stretching can assist in managing stress and symptoms related to menopause. For women with osteoporosis, exercises should avoid high-impact aerobics or activities prone to causing falls (8).

Tailoring physical activity options for older individuals based on gender-specific preferences can encourage consistent participation. For instance, offering supervised physical activity opportunities exclusively for women or older adults may appeal more to older women. In contrast, outdoor activities involving a skill-building and a competitive element are more likely to attract older men (9).

References:

- Welle, S., Tawil, R., & Thornton, C. A. (2008). Sex-related differences in gene expression in human skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE, 3(1), e1385. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001385

- Alexander, S. E., Pollock, A. C., & Lamon, S. (2021). The effect of sex hormones on skeletal muscle adaptation in females. European Journal of Sport Science, 22(7), 1035-1045. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.1921854

- Gender Differences in Training https://themusclephd.com/gender-differences-in-training/

- Training Differences: Men and Women https://8fit.com/fitness/training-differences-men-and-women/

- How Men and Women Respond Differently to Exercise https://www.austinfitmagazine.com/November-2019/how-men-and-women-respond-differently-to-exercise/

- National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, World Health Organization: Global Health and Aging: NIH Publication no. 11–7737; 2011.

- Kendall, K. L., & Faurman, C. M. (2014). Women and exercise in aging. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 3(3), 170-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.02.001

- Mishra, N., Mishra, V., & Devanshi. (2011). Exercise beyond menopause: Dos and Don′ts. Journal of Mid-life Health, 2(2), 51. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-7800.92524

- Van Uffelen, J. G., Khan, A., & Burton, N. W. (2017). Gender differences in physical activity motivators and context preferences: A population-based study in people in their sixties. BMC Public Health, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4540-0

• Body Type

Each one of us possesses a unique genetic blueprint that shapes our physical structure, including our skeletal frame and body composition, such as the distribution of fat relative to muscle. Skeletal structure grows and changes only up to the point at which we reach adulthood, at which point the growth plates in our long bones close, preventing any further growth. During puberty, hormonal changes lead to the development of distinct male and female bodies, primarily for reproductive purposes.

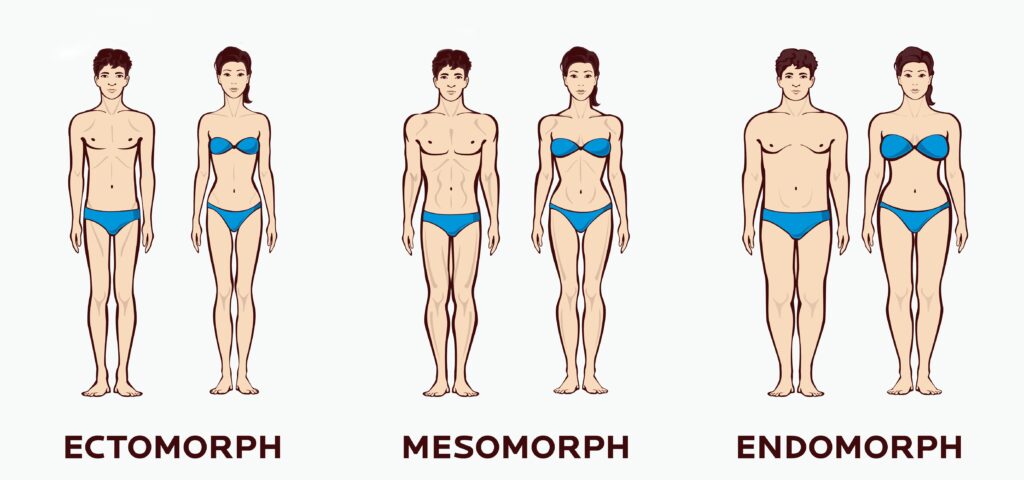

After puberty, people tend to exhibit one of three generalized body compositions, commonly referred to as body types: endomorph, ectomorph, and mesomorph. It’s important to note that individuals are commonly a blend of more than one type and fall uniquely on a spectrum somewhere between these three extremes. To determine your body’s natural metabolic state, a good reference point is how your body appeared during late adolescence or early adulthood. Over the years, lifestyle factors like diet and exercise routines, and life events like pregnancy and menopause can alter your body type, so you may not recognize yours right away.

Each body type responds differently to various types of exercise. Recognizing your body type and understanding how different workout approaches affect it can help you tailor your fitness regimen to leverage your inherent strengths and predispositions, enabling you to reach your fitness goals more efficiently. For example, someone with an ectomorph body type will respond differently to exercise than an individual with the robust and muscular build of a mesomorph. Conversely, an endomorph, characterized by a more compact and solid physique, might encounter challenges in achieving the slender, lithe appearance of an ectomorph. As an example, an ectomorph may find it easier to lose weight with cardio exercises but struggle to gain muscle mass through strength training.

For more information on exercise and body type, read “Just Your Type: The Ultimate Guide to Eating and Training Right for Your Body Type” by Phil Catudal and Stacey Colino (2019).

Additional resources:

• Body Composition (Obesity)

Maintaining an active lifestyle is essential for everyone’s well-being, but overweight individuals should be mindful of certain risks and hurdles before starting an exercise routine to safeguard against potential injury. Consulting your doctor before commencing any exercise program, especially if you have underlying health conditions, is essential to determine the safe type and level of physical activity suitable for you.

Cardiac Concerns

Individuals dealing with excess weight often face additional health issues like high blood pressure, heart disease and diabetes, which may require thorough medical assessment before engaging in fitness assessment. However, healthcare providers often recommend exercise for those with heart problems as it strengthens the heart muscle, improves blood circulation, helps lower blood pressure, and supports weight management. Vigorous exercise can temporarily elevate blood pressure, posing risks for obese individuals with heart conditions. It’s crucial to heed your doctor’s guidance on the intensity and duration of exercise and immediately halt activity if you experience chest pain.

Respiratory Challenges

Obesity can cause breathlessness even after minimal physical activity due to the heavier chest wall and visceral fat, restricting full lung expansion. If you encounter breathing difficulties during exercise, it’s important to stop and consult your doctor before resuming your workout routine.

Joint Injuries

Carrying extra weight increases the risk of exercise-related injuries as it places added stress on the lower back, hips, knees and ankles. It’s advisable for individuals with excess weight to steer clear of high-impact activities like jogging to prevent injuries that could impede mobility. Opting for low-impact exercises such as swimming or water aerobics is much gentler on the joints while remaining effective for cardiovascular health and weight management.

For those with pre-existing musculoskeletal or orthopaedic conditions and limitations in exercise capacity, adjustments to the fitness assessment procedure might be necessary.

Heat Exhaustion and Dehydration

Individuals with excess body weight often struggle more with regulating their body temperature, increasing their vulnerability to heat exhaustion. To prevent such strain, it’s advisable to avoid outdoor exercise during extremely hot weather, opt for light clothing during workouts, and ensure consistent hydration even if you don’t feel immediate thirst. Due to difficulties in regulating body temperature and potentially increased perspiration, heavier individuals are more prone to dehydration during intense exercise. Maintaining hydration by drinking ample water before, during, and after your workout is crucial to prevent dehydration.

Weight-friendly Exercise Recommendations

Embarking on an exercise program when classified as obese and leading a sedentary lifestyle can feel overwhelming. Understandably so, as certain exercises may cause discomfort or pain due to added strain on the lower back and joints caused be the extra weight. The transition into an exercise routine needs to be gradual and well planned.

There are many exercises that you can do at home without any equipment. However, I strongly advice joining a gym or using free online resources (YouTube videos, etc.) to try different types of exercise. Here are a few exercise options that will enhance physical endurance, and can assist in weight management when combined with a sensible diet.

1. Walking

Walking is a popular starting point for exercise. It’s free, there is no equipment involved, and can be done almost anywhere. Walking is a low-impact exercise ideal for enhancing lower body strength and mobility, and even walking at a slower pace burns more calories when carrying extra weight due to increased energy expenditure. However, if you are experiencing knee, back, or hip pain, talk to your doctor about it. You might benefit from working with a physical therapist or exercise professional to customize a suitable fitness routine for you.

2. Swimming and Water Aerobics

Exercising in water offers multiple benefits and is a great way to ease into physical activity. Water makes your body feel lighter, allowing you to burn calories without straining your joints and bones. Swimming and water aerobics provide an excellent full-body workout that improves cardiovascular health and builds core strength. For individuals with weight problems, swimming offers the added benefit of staying cool in the water, so they are able to workout for longer than possible in other environments.

3. Cycling and Stationary Bikes

Biking, whether outdoors or using a stationary bike, is an efficient way to boost fitness while putting less stress on your joints than walking or jogging. For individuals with back or joint issues, a recumbent exercise bike with a backrest can provide more support. It’s especially beneficial for those lacking core strength due to excess weight.

4. Strength Training

Contrary to popular belief, incorporating strength training, such as lifting weights and resistance exercises, alongside cardio is crucial for fat loss. Strength training increases metabolism, leading to more calories burned. It also strengthens muscles and tendons, reducing the risk of injuries during cardio workouts. Correcting posture issues, enhancing joint flexibility and range of motion are additional benefits.

Starting strength training at home is feasible, but joining a gym will definitely offer better support and more options. Aim for at least three sessions per week, each lasting at least thirty minutes.

Note: Initially, the scale might not reflect weight loss due to muscle gain, which weighs more than fat. However, your body will gradually become more toned with each workout.

5. Stretching / Flexibility Exercises

Integrating flexibility exercises into your daily routine is vital for maintaining joint mobility and injury prevention. Stretching reduces muscle soreness and minimizes the risk of injuries. It might initially be challenging due to tight muscles or excess weight, so gradual progress is crucial. Warm-up before stretching and avoid jerky movements to prevent strain. Hold each stretch for 15-30 seconds and repeat several times on each side.